Lessons from the La Traviata avalanche accident in Canada

I had the opportunity to speak to Ken Wylie several times over the last few months and attended a webinar he hosted – during which his inquisitive attitude and humility struck me, along with his many years of hard and honest work on himself. This article is not about trauma dumping or trauma rehabilitation, it is about transformation, and the adventure of taking our lived experiences from the mountains and turning them into valuable introspective tales that help ourselves and others to heal and learn. The accident should never only be tragedy. As Victor Frankl puts it: ‘Suffering can have a meaning or a purpose, if you transform into a new person’.

Ken Wylie

Ken Wylie (1965) is an IFMGA mountain guide living and working in Canada. In 2003 Ken was involved in one of the largest avalanche tragedies in recent North American history. He survived, but the whole accident and its aftermath made him examine his work as a mountain guide, and himself as a person. He later expressed that on the day of the accident, he had reservations about the route and snow conditions but felt unable to voice his concerns due to the hierarchical dynamics between him and the lead guide. Afterwards Wylie grappled with the psychological impact of the tragedy.

In his book “Buried” (2020), Wylie describes the tragedy and unpacks the horrible outcome and his co-responsibility. He has also chosen to share these insights and experiences with and beyond the professional North American professional mountain guiding community, delivering key note speeches for large corporate conferences on topics such as risk management, responsibility and how to improve safety.

Throughout a long and painful process of exploring and becoming aware of the realities of that tragic day, Wylie has persisted in trying to bring more resolution to our view of the human factor. Taking it deeper, teasing out the uncomfortable details on a personal level, looking for the bigger patterns. And openly sharing the lessons learned.

Website from Ken for Mindset Awareness for Risk Management.

How is it that even professional mountain guides become part of the avalanche statistics? All the expertise, knowledge and skills still does not prevent us from involvement in an avalanche disaster, or any other mountain disaster for that matter. Sometimes the red flags are really obvious to the savvy professional. Even so, we know that there are many ways to deny those red flags we sometimes so clearly see, know or feel, and continue our course of action.

But, beyond the often-cited human factors like habituation to risk, terrain familiarity and accumulated residual risk, sometimes there may be even more at play for pros with prolonged risk exposure. We need higher resolution tools that allow us to dig deeper, looking for the potential weak layers within ourselves, often well hidden. Going beyond traditional biases and cognitive errors to closely examine also on our psychological motivations and patterns.

This is exactly what Wylie has done. In his book, Buried (2020), and in his work in HPC (high potential consequences) industrial environments he explores how inner awareness — physical, emotional, psychological, relational — is just as important as technical skill. Ken asks us to think not just about where we’re going, but also what drives us on a deeper level while going there. He’s not saying ‘ditch the tech skills’ — far from it. He’s saying: pair your technical mastery with emotional clarity, group attunement, and self-reflection. That’s where real leadership lives. It all leads to his key question ‘how do I show up?’.

Wylies personal perspective – Part 1: How do I want to show up?

(In this article we focus on Wylie’s personal perspective and the integration of all that happened. In the upcoming BergundSteigen article we’ll explore his approach and archetypal model to become more aware of the potential and personal pitfalls in our decision making.)

What were your first thoughts directly after being dug out of the avalanche debris?

A deep feeling of ‘how am I gonna get out of this one, as a guide, as a person?’ But there was no getting out of it. I’d really done it this time. I had never run the idea in my mind being in an event like this, and survive. I always thought that if something really bad would happen, I probably would’nt have to live with the consequences. It was a shock that I lived. I had to deal with the consequences.

No escape possible, apart from suicide or becoming an alcoholic. I never allowed myself to imaginea surviving with consequence outcome. Among a whole list of lies in my approach to the mountains, that was the biggest one. . . a form of denial. I think that if I had have imagined an accident where I survived, I would have taken my approach a lot more seriously. Fundamentally I was embodying a very immature, adolescent approach, one where I failed to consider the worst possible outcome.

You were only the assisting guide and not bearing final responsibility – what made you realize you no longer wanted to hide in the shadows?

Being the assisting guide, not the lead guide, I had a sort of get-out-of-jail freecard. After the accident the lead guide took all the heat. I could have hidden, and move on with the rest of my life, like so many advised me to do. Like I tried to do. But that became totally unsustainable for me. In 2008 – 6 years after the avalanche – I recognized I was living a lie and that is when I started to figuring things out. My community thought that I went nuts because I was not taking the normal path of forgetting. Essentially what happened was that i needed to stop everything I was doing and start paying attention.

Paying attention to what?

There are so many facets to it, when I got out of bed in the morning, and looked in the mirror in the bathroom I didn’t like who I saw. I started to realize that it was probably a feature in my life long before the avalanche and that it was probably one of the causes. I was so hell bent on mountain adventures because I just wasn’t enough to myself. The mountains became my refuge, my escape from the pain ‘down deep’ of not being enough. Achievement became my sense of worth and that was a hazard.

„In 2008 – 6 years after the avalanche – I recognized I was living a lie and that is when I started to figuring things out.“

Ken Wylie

What do you mean with not being enough to yourself?

I was denying aspects of myself that knew better. Some may question this because I am looking now at the tragedy with hindsight. But, the morning of the tragedy I woke up and I wanted to quit right away but told myself to hang in until Friday. The best part of myself knew that we were headed for disaster, and I silenced that part of me because I had so little respect for my own internal guidance system. If I was enough to myself, I would have respected myself enough to follow through with what I knew was right, and quit working there.

So you knew the route you were on was dangerous?

Yes. Definitely. And the problem was not only the weakly bonded snowpack, it was also a failure to recognize the hazardous dynamic with the lead guide and owner of the operation in the previous weeks. In my experience, he, and the operation adhered to a very strong hierarchy. There was no collaboration.

During the weeks I worked there, discussion about the guiding day and what anyone else might think or feel about the objectives chosen by the lead guide in relation to the client needs or snow and avalanche conditions, were not cultivated. In every interaction where I had a different opinion about what should happen, my ideas were not respected or ever implemented. This led me to believe, which was untrue, that I had no choice. The truth was that I had a choice, and that choice would have required quitting work on the spot.

Hierarchies, I now understand to be unethical in situations where consequences are shared. This is to say that when we are all exposed to something undesirable, like harm or death, we must be given or claim our voice. There are two ways to remedy an inappropriate hierarchy. One remedy is from the leadership: recognizing the equal exposure to consequence and cultivate a free and open assessment of conditions and choosing together appropriate objectives in relation to those conditions.

The other way is to challenge those in positions of leadership when the choices are too aggressive, even if it requires walking off the job or refusing to participate. Regardless of experience, in High Potential Consequence situations or environments, everyone deserves a choice. Choice must be given and if it is not, it must be taken. There is a lot to say here with respect to pushing ourselves or being pushed so we grow. But these choices must happen freely and in a respectful environment.

Ironically, after the event I was told that I was part of a team and that I should have spoken up if I was uncomfortable with what we were doing. This was painfully true. On the day, I had given up my voice because I believed it to be pointless. It was not. Losing one’s job is not the end of the world, pulling bodies off the mountain is.

What is really liberating now is that when people say ‘you guys were really stupid going there’ my response now would be ’you’re absolutely right. it was the dumbest thing that I’ve ever done’. And I know now why I went there. And it’s way deeper than just being careless. I denied my better self, was afraid to speak, I failed to connect, I lacked self awareness, I deceived myself, I intellectualized instead of using my intuition and I stepped into a situation that was on a trajectory to disaster.

When we see some else’s mistake we often see only the last decision that they made, and little do we know of the hundreds of small steps, compromises, events, experiences and decisions that brought them to that point. At any point if you can see the trajectory of it, and say ‘I don’t like it’ you can choose to exit. I lacked the social courage on that specific day, to say ‘I see where this is going and I am not going to participate in it.’

My friend Brian Spear said it best; “Hierarchies lead to chaos and they are the only way out of it.” So in a chaotic situation, we need uncompromising leadership to get ourselves out of it. So often, power is misapplied. In situations where choice is not given, and we are exposed to verbal or emotional abuse or being ask to do something unethical, we must be willing to hold our boundary. I knew the risks, saw the red flags and possible consequences but did not speak up that day. And thus co-guided 7 people to their deaths.

How do we come back from failure, from catastrophy ? How did you?

What we often don’t understand in our society, is that when something like this bad happens, it is an opportunity to learn. I am still learning what has happened. I was a 38 year old boy when I was dug out and I was being asked to become a man. When we as humans experience these tragic things, the wise way to experience this is by integrating them, not to run away from them.

There are so many ways to fall into denial, to distract yourself and just continue your life. We all face things that can scare us to the core of our being. the better question is: How are you going to OWN this, INTEGRATE it? And make this something that becomes something valuable. I am paraphrasing Joe Campbell* when he says ‘Let me come back with a gift to the community’.

What did you discover?

The mask I was wearing needed to come off. I needed to start discovering the truth about everything related to myself. I wanted to discover why I was so engaged in adventure, why I became a mountain guide and and how I participated in the tragedy. We often don’t ask the “why” of adventure. It seems like a silly question that can easily be answered with the word fun. But the “why” suddenly becomes the most important question after a tragedy. I didn’t know what these truths were at all and it terrified me. I was in great pain and very few people knew how to deal with me. I was feeling so alone at that time.

„I knew the risks, saw the red flags and possible consequences but did not speak up that day. And thus co-guided 7 people to their deaths.“

Ken Wylie

It felt like I am going off into the abyss. No guidebook no waypoint no map and no belay. The biggest loss was my innocence, and I think that ignorance is incredibly empowering. That’s why we see young adventurers doing incredible things. The link to consequences isn’t there yet. Or only partially. That is a beautiful thing, but also a dangerous thing because it can lead to tragedy. I lost the idea that adventure is only beautiful. I now know that it can turn into something horrible, in an instant.

Then you started writing a book

Yes, I started writing the book ‘Buried’ – at the start it was all about why I was not to blame and not accountable. But that did.NOT work. I began to see patterns in my life of adventure that were potential lessons in acceptance, courage, connection, self awareness, and truth and it became very clear that my failure to meet the mark, long before my experience with the avalanche was a feature in my life that I denied…

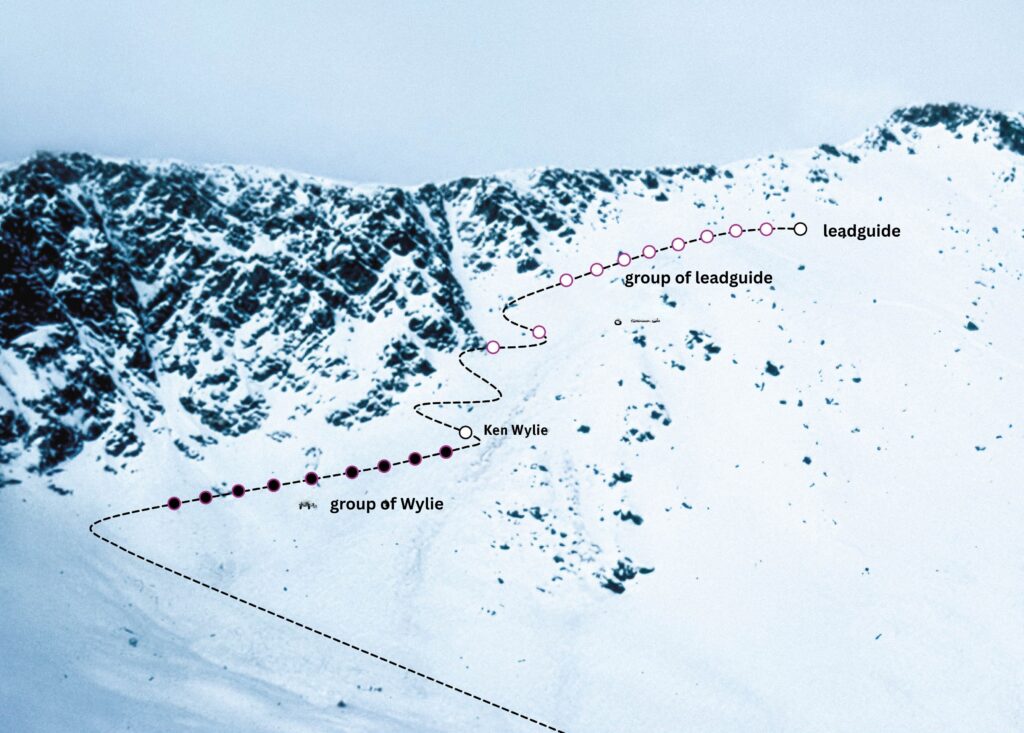

La Traviata avalanche

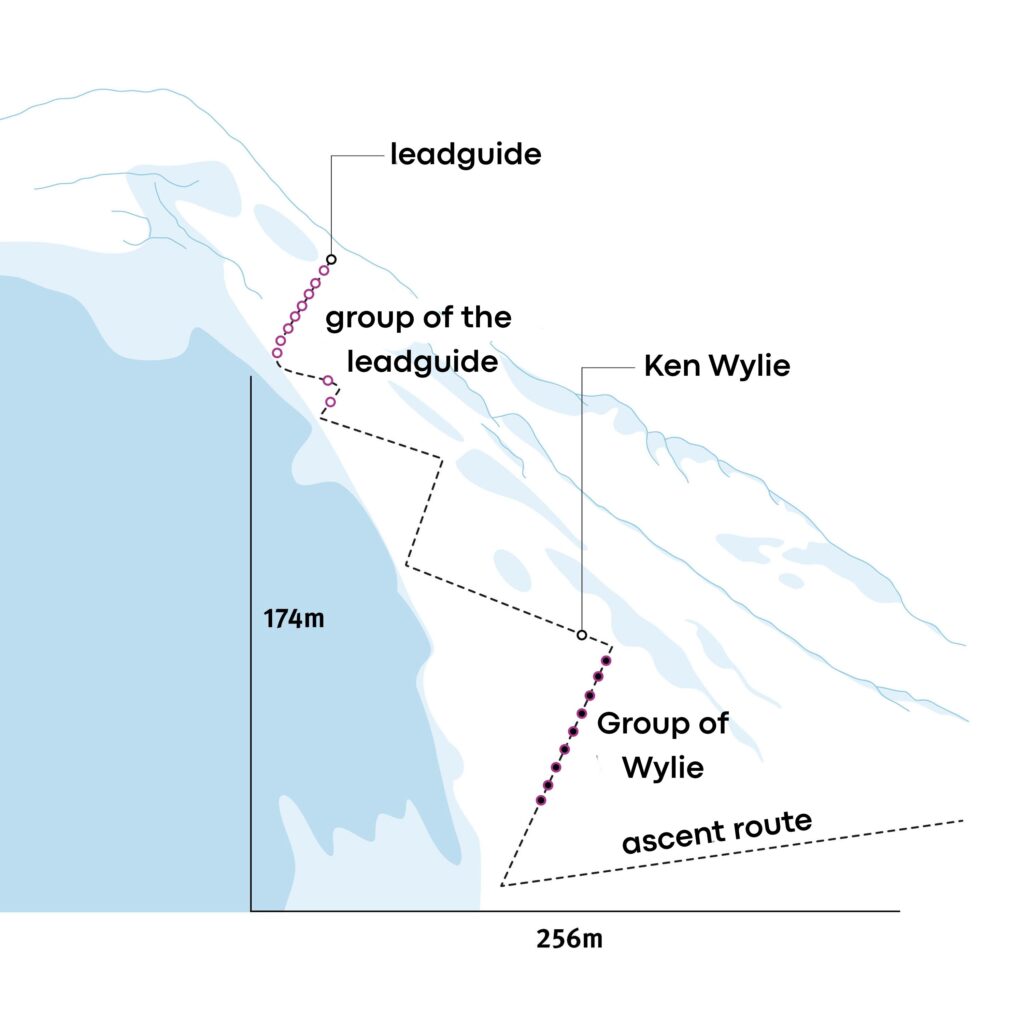

The La Traviata avalanche incident occurred on January 20, 2003, during a backcountry ski trip on the Durrand Glacier in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia. It was one of Canada’s deadliest backcountry skiing incidents ever, resulting in the deaths of seven experienced skiers. Six others were rescued or self-extricated. The group consisted of 19 skiers on a guided trip, led by a renowned (Swiss) guide and Wylie in the role of assistant guide. The larger group had formed two smaller subgroups and were ascending the “la Traviata” couloir when the avalanche occurred.

The avalanche was a large slab avalanche, up to 280 cm thick in some areas, estimated at size D3, and with a terrain trap at the foot of the slope. Its estimated debris volume (~47.000 m³) and total mass (~19.000 tonnes). An independent analysis, commissioned by victims’ families after the disaster – questioned the choice to ascend the 36° to 37° and 310-meter long couloir, given the day’s “considerable” (3) avalanche danger and the unconventional practice of having multiple skiers on a steep slope simultaneously. The slope was wind-loaded and the snowpack conditions, were unstable due to a persistent weak layer from early winter. This layer was buried under subsequent snowfalls, creating a dangerous setup for (deep) slab avalanches.

Wylie prefers to state the names of the seven victims who lost their lives, to go beyond the statistical figures and emphasize that this is about real people who lost their lives, a great tragedy for their families and loved ones.:

- Kathy Kessler (Truckee, California)

- Dave Finnerty (New Westminster, BC)

- Vern Lunsford (Littleton, Colorado)

- Jean-Luc Schwendener (Canmore, Alberta)

- Dennis Yates (Hollywood, California)

- Naomi Heffler (Calgary, Alberta)

- Craig Kelly (Nelson, BC)

The La Traviata avalanche profoundly affected the (Canadian) mountain guiding community. It prompted a reevaluation of guiding practices, emphasizing the need for open communication between guides and between guides and clients. The incident highlighted the dangers of hierarchical decision-making and underscored the importance of considering human factors in risk assessment. The tragedy also contributed to the establishment of the Canadian Avalanche Centre (now Avalanche Canada) in 2004, aiming to enhance public avalanche safety education and forecastting.

Can you give an example of the denial you were in?

I denied that adventure had meaning that was my responsibility to unpack. My penchant for denial showed up after the avalanche too. . .I had so stifled any memory, any connection to the avalanche experience, that I couldn’t even name the people that lost their lives. It’s crazy how powerful this process of denial works. I had completely objectified the people that died. They became just a number for me. How do we do that as a culture? How do we go back and put names and feelings to things that we’ve experienced? Because they are real.

I wasn’t able to remember the names of the people that died, honour them, getting in contact with their families. And that was so painful, because I was trying not to care. When I teach my students in adventure sports risk management, I teach them besides the technical skills to go on a journey, discovering and becoming aware of the decisions we are making, often in shadow and bring everything into the light. Become conscious of what is being done, and that was what I did not do that day in January 2003.

To look at it from a wider perspective – you somewhere say we also need to reframe the ‘outdoor narrative’?

In my view we are being asked through mountain adventure, to become our best selves, not to fuel our egos. Everything you will read about the human journey and what we’re here for will encourage you not to fuel your own ego, it’s a daily practice of becoming aware. This is what adventure is about for me now. It has only little to do with what we achieve. And everything to who we become. And if that is the journey of adventure, then we don’t need to justify anything. People will notice.

If we mature through the process of adventure, we will make better decisions. We come back better, resonating maturity, mastery and friendliness, bringing something valuable to our communities.

It is very important to be aware that we are also at risk with behaving in an immature ways, where we fully claim our success as being ours, and never owning our failures. That is adolescent behavior. I see outdoors and adventure space is actually calling us to become more human. A sort of reframing the narrative of the outdoor sports – from heroism to learner, becoming more human is to be of service to others.

The adventure experience is meant to teach us to find a way that opens up our options instead of decreasing our options. The most important thing is that adventure is real. So much is virtual or modified these days. we need to be in consequential environments where we can really exercise our perceptions, our senses, and embody our choices, but also learn to question our perceptions and invite the perceptions of others.

Making decisions that have real consequences and learning from them. The outdoors are great for that. We have to allow ourselves. Accepting the hardest things about the decisions that we’ve made in the mountains and shining a light on them. We say we want freedom. But we are emprisoning ourselves when being in denial, it costs so much energy and joy in life.

Thanks for your time and sharing Ken.

References

- Campbell, Joe: The Hero’s Journey, Harper Collins 1990

- Frankl, Viktor E.: Trotzdem Ja zum Leben sagen: Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager, 1946 (deutsche Ausgabe), 1959 (englische Ausgabe).

- Penniman, Dick & Baumann, Frank: Case analysis – The SME Avalanche Tragedy of January 20, 2003: a Summary of the Data, 2004 – https://docslib.org/doc/799021/the-sme-avalanche-tragedy-ofjanuary- 20-2003-a-summary-of-the-data?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Trenkwalder, Pauli: ÖKAS – Analyse Berg Winter 2024–2025

- Van Galen, Anne: We really need to do better; bergundsteigen #128, Herbst 24

- Wylie, Ken: Buried, updated edition, e-Book, Canada, 2020

- Wylie, Ken, website – archetypal.ca